Nearly 12 years ago, before I had fully embraced Diabolism but had been involved in the occult for nearly two decades, I flirted with Christian Gnosticism. I wrote a manuscript at this time, attempting to produce a gnostic catechism that would outline where Gnostic Christianity and orthodox Christianity diverged and where they agreed. I let a close friend read this manuscript at the time. He was impressed with the writing, but noted, “You never mention salvation. Christ comes to save, right? What does this gnosis save you from?”

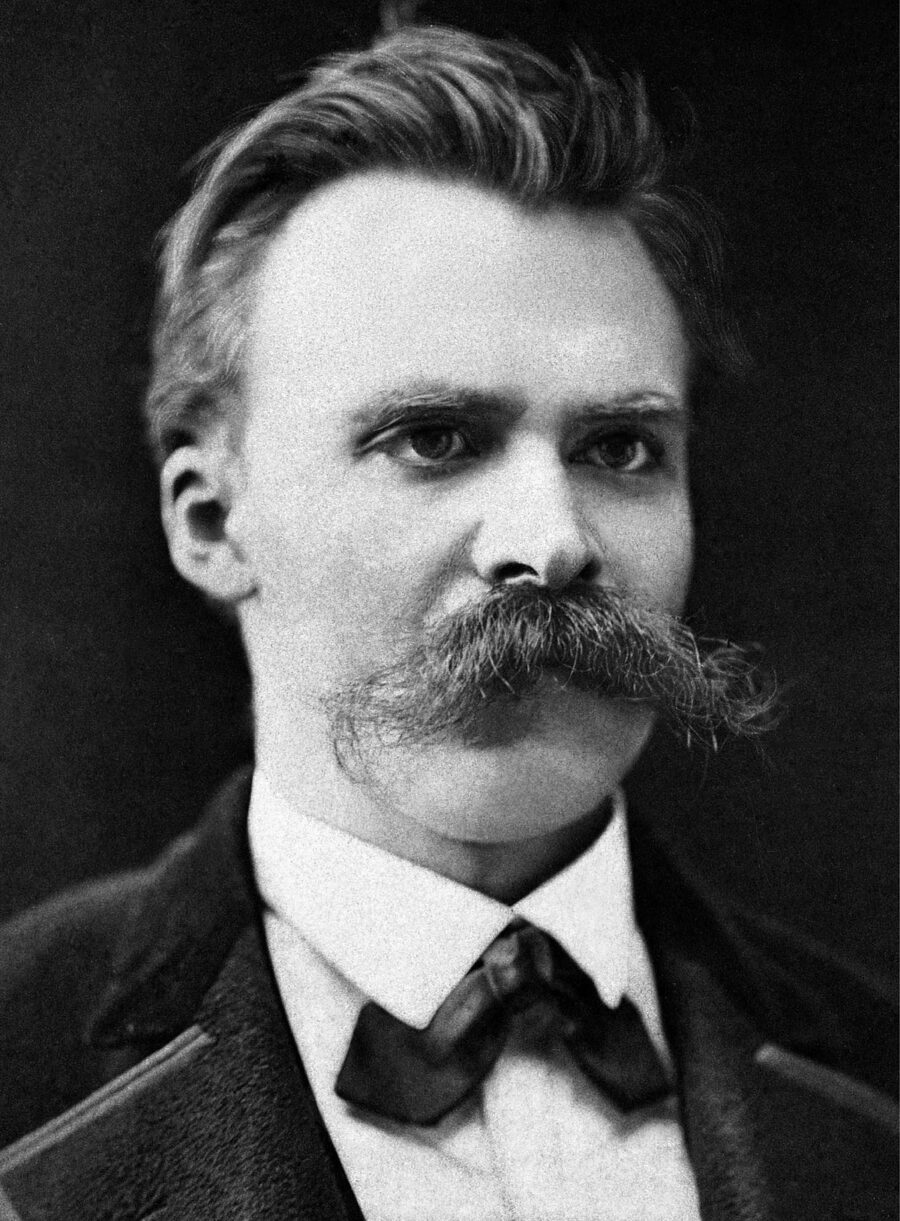

That same question can be asked about Satanism and the western Left Hand Path, and Bilé tells us we can find the answer in Nietzsche. It is nihilism. What Satan can save us from is life destroying nihilism.

This may be confusing for some readers, who have perhaps been led to believe that Nietzsche was a nihilistic philosopher, rejecting any notion of objective norms and morality. But this association of Nietzsche with nihilism is only a half-truth. For Nietzsche, there were two forms of nihilism: negative or passive nihilism, which was to be opposed, and positive or active nihilism, which is part of the necessary path to the Overman.

Bilé explains that the origin of our current malaise and passive nihilism (the culture of what Nietzsche would call the “Last Man”) has its roots in the Platonic and Christian obsession with a search for truth. Unfortunately, he never formally defines what he means by truth, but it is apparent by how he talks about it in chapter three that what is not meant is factuality. Rather, the truth Christianity, and thus western civilization, has been obsessed with is analogous to the Platonic world of Forms. He writes that, “Religion, philosophy, and even science answer to our impulse toward self-preservation, the will to truth is a consequence of this trepidation and terror evoked by and absence of worldly meaning.” Rather than a pursuit of fact as opposed to fiction, what Bilé means by the “will to truth” is the search for something eternal and unchanging in a world that by definition is transitory and ever-changing. It is the pursuit of a world of pure Being, which, since reality is a realm of Becoming, can never be found in this world.

“As mentioned above,” Bilé writes, “the ascetic ideal breeds the will to truth, which seeks the affirmation of another world by denying this one. The ‘truth’ as a categorical commitment places higher importance on the elusive eternality than on life itself; illusion is elevated above prudential goods.”

This pursuit of Truth sows the seeds for the passive nihilism western culture is now in the grips of. Since an eternal unchanging Truth cannot exist in this world of flux in which we live it must be put off in a metaphysical hereafter. But as science makes the existence of such a realm of Truth all the more improbable, not only do we lose faith in that metaphysical world, we are left bereft of any value in or attachment to the actual world of nature, and in any interest in forming a morality that will allow us to positively live in it. As Bilé writes, “Man’s yearning for suprasensorial truths becomes a self-immolating and self-refuting force: where artifice of ultimacy is lost, meaning itself is lost; and where meaning is lost, the beingness of Man is lost.” A god of Eternal Truth will never lead to world affirmation, only world weariness. As Nietzsche wrote, placing ultimate value in eternal Truth will eventually lead to a poisonous pessimism, “which is an expression of the uselessness of the modern world.” In fact, Nietzsche equates Nihilism with Christianity in his aphorism, “Nihilist and Christian—this rhymes.”

Bilé contrasts the worshipper of Eternal Truth to the Satanist, who “does not forfeit the natural world for the neo-Platonic heavenly but abandons reason to engage in a depositional process, a drawing down of God into the Beast.” Here again we are confronted with the image of the satyr, the Baphomet, who combines the heavenly and the earthly in one being. As an antichrist, the Satanist is moved to oppose Christianity’s moral valuations: the inversion and obliteration of hierarchy, whereby what is vulgar and common is valued over what is strong and elite; communism over individualism; the valorization of pity; esteeming the hereafter instead of what is present now. All these are anathema to the servant of the Devil.

It is through Lavey that Bilé presents a blueprint for how we can wage war against the Crucified One. As said earlier, Lavey consciously drew on Friedrich Nietzsche when developing his own infernal philosophy. Nietzsche is famous for writing about the coming Overman, and what such a man or woman might look like, but he is perhaps just as famous for never having laid out any sort of program by which the Overman could be realized. Lavey seeks to remedy this problem by setting out a plainspoken moral and ritual practice by which an individual may save the godhead within themselves.

There are a few ways in which Lavey takes up the torch Nietzsche left behind. Firstly, Laveyan Satanism:

seeks out the inverse of virtue; it revaluates the vice of Christianity, so that they become newfound virtues. Modesty becomes indulgence, and anti-sensual restrictions inspire sexual expression—pride, vengefulness, and avarice all become positive attributions, associated with Satan and the core tenets of Satanic identity.

Secondly, Laveyan Satanism rejects the emphasis on the spiritual and places all value squarely back in natural existence. By rejecting the transcendent, Lavey makes the natural world “the good world, a world of transition, change, and chaos, all of which are viewed as immoral according to Christian moral valuations.” Rather than the soul, the Satanist becomes primarily concerned with the needs and urges of the human body. Nietzsche would approve, as he claimed the body was “a more astonishing idea” than the human “soul.” For Lavey, epicurean pleasure and physical indulgence are ends in themselves and need no further moral justification.

Thirdly, where Christianity emphasizes pity (the meek shall inherit the earth), favors the poor majority over the noble minority (blessed are the poor…but woe to you who are rich, for you have already received your comfort), and emphasizes self-denial (you must take up your cross daily), Laveyan Satanism values meritocracy, power, and the elite over the downtrodden. “Blessed are the strong,” Lavey’s Satan declares, “for they shall possess the earth—Cursed are the weak, for they shall inherit the yoke!” Where Christianity preaches forgiveness and love of enemies, Lavey preach lex talionis—an eye for an eye.

Fourthly, Laveyan Satanism seeks a mode of living that lies beyond common conceptions of “good and evil.” We see this in Lavey’s rejection of there being something that can be called white magic. “There is no white or black magic; both compassion and hate are to serve the ego.” In fact, Lavey says, morality is never anything other than self-serving. What we proclaim as right is truthfully what we deem will best serve our self-interest (though whether we are accurate in those judgments is another matter entirely). Social scientists have begun to come around to this idea, some going so far as to argue that most of our moral judgements are actually post hoc justifications for our behavior, and rarely as rational and dispassionate as we like to pretend.

The rest of Friedrich Nietzsche & the Left Hand Path is largely devoted to considering how the Satanist, with both Nietzsche and Lavey informing their practice, can overcome the nihilism that kills and embrace the nihilism that breeds life. As I want readers to get ahold of the book for themselves, I will not exhaustively consider these concluding sections. Primarily, such an endeavor involves making oneself the locus of their spiritual life, antinomianism, carnal indulgence, moral and philosophical skepticism, and creating meaning through will in a world that is harsh and unforgiving. “Equipped with the transvaluation of values,” Bilé writes, “the Satanist adopts a Dionysian pessimism, a pessimism of strength, a pessimism of the future that ‘destroys all other pessimisms,’… Like the overman, the Satanist will always be ‘without a master” — a radical individualist who becomes his own redeemer.”

Diabolists would be well served to read this book, think about it, and then read it again. I do warn the prospective reader, however, that this book focuses almost entirely on Laveyan, rationalistic Satanism. Not to say that it is hostile to theistic Satanism, but that isn’t its focus, and some passages rub against what I consider the values and conclusions of traditional Devil worship. In fact, one of the questions I am left with is how much of this book reflects Bilé’s own philosophy, and how much of it is an academic exercise? Bilé is openly theistic in his Satanism, so I am left to wonder why he would write a book that is so secular in its perspective.

Whatever the reason, readers should be cognizant of the fact that the book is largely written from an atheistic point-of-view, and will thus require some small interpretation on their part.

The larger issue my readers will have to consider for themselves, though, pertains to the very Left Hand Path itself. I have never considered the Diabolist’s path to be solely that of the Left. The Devil’s is a Crooked Path, meaning that we cross between the Left and the Right as needed, learning the lessons of dominance and submission, mercy and severity, darkness and light. Nor do I find much worthwhile in the idea of absolute auto-theism. The traditional Satanist is certainly called to a path of apotheosis, pursuing their Will and manifesting as much of their divine self as they can at any moment, ideally growing into an ever-greater vessel for the daemonic spirit they have been given. But we do have a Master and Mistress. We worship a god and goddess. There is a Law both within and outside us. We are stars, yes, but we exist in a universe full of them. And the language of becoming an “isolate intelligence,” which comes from the Temple of Set, frankly leaves me cold, for it sounds much more like escaping reality and our humanity than embracing it. We are social creatures, who find our highest sense of fulfillment through our interaction with the social and external world. There is nothing that exists in isolation. We are all part of the web of existence, and what affects an individual part will invariably come to affect the whole. The opposite is true as well. The only way I can conceive of transcending the interdependence of existence is to destroy everything else that isn’t you. The logical conclusion of absolute autotheism and seeking to become an isolate intelligence seems to be anti-cosmicism, which by definition is not only self-defeating but, again, the opposite of embracing reality for what it is.

What is the use of becoming a god if you must destroy everything you love and enjoy and everything you are to do it?

I am also skeptical of the claim that there are no objective moral principles whatsoever. If there is no foundation to morality (albeit as grey and fluid as that foundation may be) why is there any reason for Nietzsche and those who came after to him to reject the passive nihilism he so forcefully rails against? Why prefer the Overman to the Last Man? Why do we value strength, nobility, creativity, and individuation over their opposites? Nietzsche cares about these things because, to his mind, they are the basis of life and health, but if good and evil are entirely subjective, what basis is there to object to preferring slavery over freedom, decadence and decay over growth and fruitfulness? Perhaps the argument could be made that it isn’t a matter of morality, merely of aesthetic taste. But if that is the case, who gives a shit about Nietzsche’s preferences? The truth is, the things Nietzsche (and by extension Lavey and Satanists more generally) value imply moral judgments.

As with the word truth, what is meant by “objective morality” may be the real bone of contention. The co-host Sitch, from the Sitch and Adam podcast, has an axiom known as Sitch’s Law, which asserts that the majority of political and philosophical disagreements are really just arguments over definitions. Perhaps what Bilé means by objective morality I would call something else. I concede that all morality is in some sense subjective, but to me the subject can just as easily be a species as it can an individual. And while particular modes of moral conduct may make more or less sense in specific situations, that doesn’t negate the existence of the virtues those modes are aiming to embody.

Regardless, it is clear to me that even if we cannot point to an absolutely objective morality, that doesn’t entail that all moralities are created equal.

Lavey clearly assumes a particular moral foundation in The Satanic Bible. Non-aggression; respect for the property and rights of others, including animals and children; sexual freedom; the importance of consent; and the right to self-expression are just some of the moral principles contained, implicitly or explicitly, in The Satanic Bible. Yes, Lavey talks about being ruthless against one’s enemies, but this is always in the context of an individual’s rights having been violated. Never does he suggest that a Satanist should be the unprovoked aggressor. Yes, Lavey does make use of “might makes right” language and sees reality as bluntly Darwinian, but there is a tension in The Satanic Bible between extoling that which is savage and that which is noble.

Consider this, the myths we tell about Satan and Lilith have certain moral standards coded within them. Satan opposes tyranny. The fallen angels are loyal to their captain, rather than treacherous. Lilith shows courage in escaping Eden, obeying her own nature. Jehovah is condemned for his bloodlust, misogyny, and ethical narrow-mindedness. As servants of the Devil, we absolutely have a code of honor, and examples of conduct we seek to emulate.

As Diabolists we worship the Adversary. To accept the Devil’s Mark is to enter a spiritual conflict of cosmic proportions. There are forces who oppose Satan’s vision for the world, and they are our enemies. Perhaps it is true that there is no such thing as objective morality, but there is such a thing as a Satanic Morality, and it is not “anything goes.”

All that is to say, while the Diabolist must surely move beyond a vulgar conception of good and evil, we do believe there is evil in the world and seek to oppose it. If not directly then indirectly by how we choose to live in our daily lives.

I want to circle back and reiterate there is much of value in this book. A lot. For those who are looking to move beyond neophyte level Satanism, this book is a fantastic place to start. Even if you don’t agree with everything in it, it gives you formidable intellectual arguments to wrestle against. If nothing else, it helps drive home just how much nascent Christian morality (whether of the orthodox or heretical “woke” variety) most of us need to root out of ourselves.

So, I encourage you, let Bilé take your hand and, along with Nietzsche, be a guide in understanding your Lord and religion all the better.