I first encountered Shea Bilé’s work on his (seemingly now defunct) Deferred Gnosis podcast, where he explored religious Satanism with an atheist co-host. After that, I heard interviews with him on a couple of different other podcasts. On all of these he proved to be one of the most serious, erudite, and interesting voices currently vocal in Satanism. So, it was with great interest and expectation that I purchased his book, published by Atramentous Press, Friedrich Nietzsche & the Left Hand Path.

This will be less of a review and more of a close examination of Bilé’s book, but for those who are interested, it is finely written and produced. My copy is the Standard Edition: black linen covered with gold foil debossing. The pages are sewn rather than glued, which means the book should hold together well past my lifetime.

As an aside, I have mixed-feelings about the high-end occult book craze of the last decade. On the one hand, many of these books are beautiful. There is no arguing that. And there is something to be said for finely published occult tomes possessing talismanic qualities. On the other, this puts the price range of many of these books outside what some, perhaps many, occultists can afford. That may be a bug or a feature depending on your perspective. What I have noticed, however, is that this means most of these books end up in the hands of the collector and armchair crowd, rather than the people actually doing the work. As someone who takes his Satanic ministry seriously, it is the latter I am most concerned with.

And, to be blunt, just because a book contains outward talismanic qualities doesn’t mean it has much worthwhile inside.

That is not the case with Friedrich Nietzsche & the Left Hand Path. This is both a superbly written book, but a densely written one as well. Though it clocks in at only a little over 130 pages, nearly every sentence on those pages is packed with insight and meaning. This is not a book you skim through, put back on the shelf, and never touch again. I have read it three times over the past year, and still feel I haven’t mined everything in it yet. This is a book that forces you to slow down and to think. This is not a work for beginners, but for the intermediate and advanced practitioner. There aren’t enough of those out there, so they are true gems when they appear.

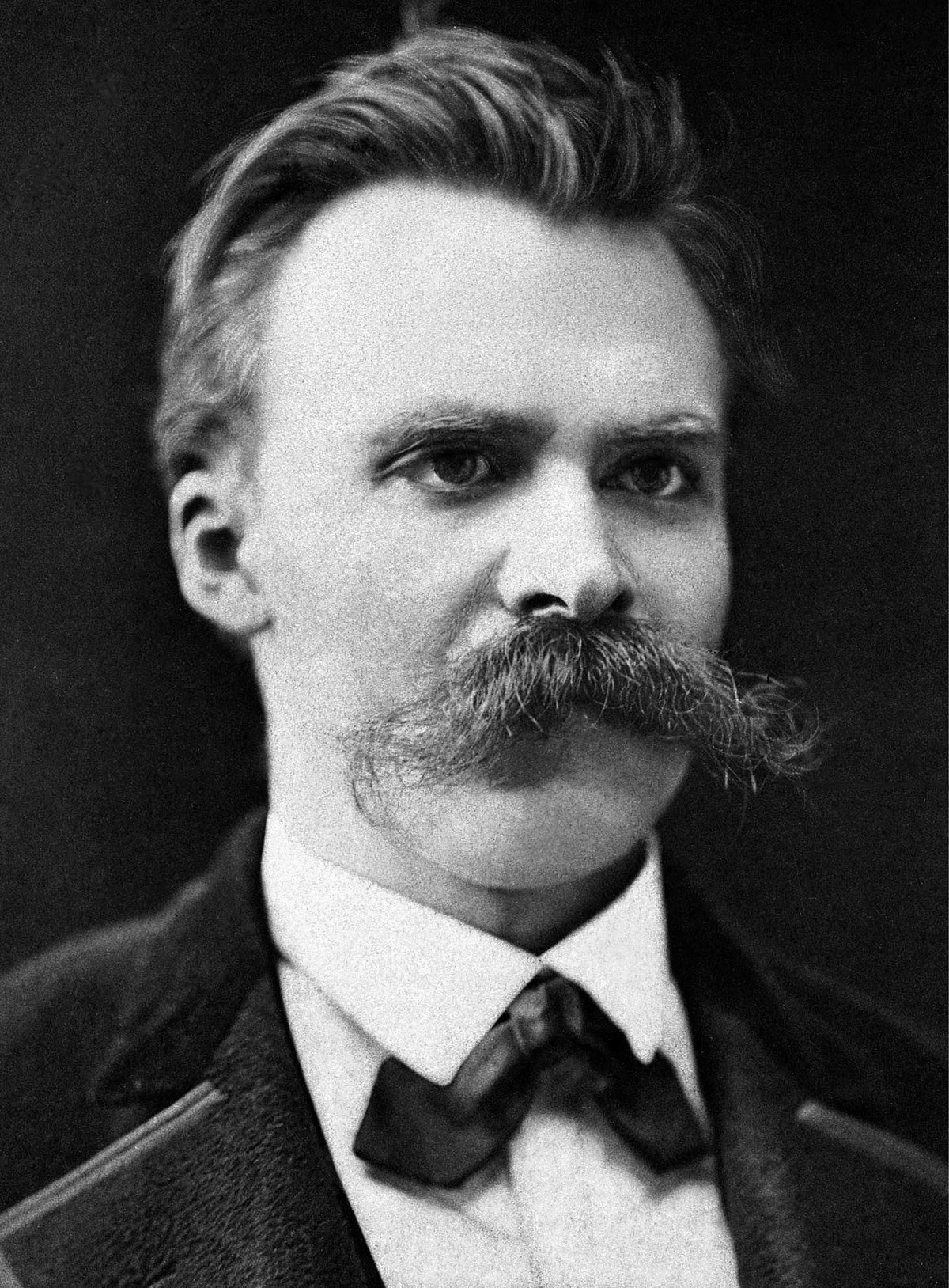

As the title of the book indicates, this book is primarily about the intersection of Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophy with the philosophy of the western Left Hand Path. Specifically, it looks at the affect Nietzsche’s work had on Anton Lavey (the popularizer of the concept of a western Left Hand Path) and the early Church of Satan. Crowley and others invariably make an appearance here and there, but Lavey’s Nietzschean discipleship is the primary concern. The Black Pope made no secret of how much influence Nietzsche had on him, and his religious Satanism is in many ways an attempt to translate Nietzsche’s insights into a viable spiritual path.

These are all solid decisions of focus. Without Lavey there would be no religious Satanism or western Left Hand Path more generally, and without Nietzsche there would be no Lavey.

For anyone familiar with Nietzsche, a question is likely to arise at this point of how organic this connection between Lavey and Nietzsche is. While the German philosopher did write a small book called The Antichrist, he had surprisingly very little to say about Satan, Lucifer, or the Devil explicitly. He certainly never recommends the Devil as a figure of religious veneration, or an archetype to emulate.

Or does he?

Friedrich Nietzsche & the Left Hand Path begins with a rather poignant and powerful epigram from Nietzsche’s The Dawn of Day. “Now I belong to the Devil. I go with him to Hell. Break, break, poor hearts of stone! Will you not break? …I am damned that you maybe saved! There he is! Yes, there he is! Come, kind Devil! Come!”

While the above is one of the few times Nietzsche has much explicitly to say about Satan, there is a figure Nietzsche holds up as a spiritual paragon—Dionysus. The god of wine and madness is a thread that runs through and connects nearly all of Nietzsche’s philosophical writing. At the opening of the first chapter, Bilé writes:

The sacred pain of a dying mother, the frenzied consumption of a child’s flesh, the penetrating gaze of holy terror, the entwined dervish of life and death, the bloodied face of a wrathful lover, the lustful revelry of a depraved people, the purifying fire and the consecrated wine—this is the divine paradox of Dionysus, the god of Friedrich Nietzsche and the god of this world.

If the phrase “god of this world” calls to mind Satan, that is right and intentional. It is a title associated with the Devil in the Christian New Testament. Bilé makes the argument that the being we know as Satan or Lucifer is a multi-faceted one. A deity who wears many masks and goes by many names. This has a tangible connection to Dionysus himself, whose visible totem of worship was often a mask nailed to a tree. Bilé says that the god of wine is clearly an antecessor of what would later become the Christian Devil. “[A]n origination borne from antinomian beauty and a contentious allure.”

For Nietzsche, Dionysus was a symbol of everything that had been lost of the ancient world when Christianity came to power in Europe. The wan, meek, and ineffectual Christ replaced the beauty, vigor, excellence, frenzy, and strength of the Hellenic world. For Nietzsche this was a tragedy, and so he sought to conjure this Dionysian force back into the world through his writing. This force was so powerful for the philosopher, Bilé writes, “he would end some of his letters with the nom de plume ‘Dionysus’—auspiciously similar to Aleister Crowley’s self-identification with ‘The Beast’ or Anton Szandor Lavey’s endearingly carnivalesque ‘The Black Pope.’”

“Nietzsche conceptualizes Dionysus as a tragic hero,” Bilé says. “The fusion of antipodal ideals—happiness and death, madness and freedom, the birthing mother and the dancing murderess…the affirmational union of the radical in-between, synthesized by the artistic and metaphysical force of Dionysus, the goat-god of tragedy and the tragic Greek myth.”

Nietzsche himself wondered, “Where does this synthesis of god and billy goat in the satyr point?” For Bilé the answer is obvious. “Here is the ‘synthesis of god and billy goat in the satyr…’: Nietsche’s Dionysus, Milton’s Lucifer, Shelley’s Prometheus, and the god of Man himself—Satan.”

So, for Bilé, whether we speak of Pan, Dionysus, Prometheus, Lucifer, or Satan we are speaking about aspects of the same spiritual being. He groups the attributes of this god into two primary forces, both in tension with one another—fire and wine.

This sense of blended of polarity is a key feature of religious Satanism’s understanding of the Devil. We see it portrayed in the light and dark aspect of Baphomet. The intellectual and carnal aspects of Satan and Lucifer. Readers who are familiar with the Brethren of the Morningstar’s Book of Infernal Prayer will perhaps think of the satanic psalm, “Annunciation.”

Behold the Lightbringer who lights the way out of bondage. Topple the mountains. Flood the valleys. All shall be put to the test. Cling not to names and images. Stability is found in motion. What use is the past but to dissolve and recombine? Search not for my paths in books. I direct my beloved by invisible means. Step lightly in your certainty. Sit boldly in your doubt. In the palace of tension, I am found.

For Bilé, Satan’s fiery aspect is his Will to Power. Lucifer is the great figure of revolution, who casts off his undeserved chains in search of freedom. And who likewise offers humanity the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge to lead us in a similar quest. He describes the worshippers of Dionysus, the maenads, in terms very much reminiscent of the folk tales of witches’ sabbaths from the late Middle Ages. Women who, in an ecstasy of freedom and fury, have thrown off all conventional morality to make contact with an existence that is deeper and more primordial.

“The Devil is an impassioned emancipator,” Bilé writes, “…because he embodies that which is sinful, unspoken desires and indulgences are associated with evil, and that which is evil is the Devil’s blessing.”

As a figure of political revolt, Satan came into his own in the 19th century, when socialists and anarchists alike appropriated the Lucifer of the earlier Romantic Satanists for their own goals. Bilé uses this well-known quote from anarchist Mikhail Bakunin to demonstrate this point.

Jehovah, who of all the good gods adored by men was certainly the most jealous, the most vain, the most ferocious, the most unjust, the most bloodthirsty, the most despotic, and the most hostile to human dignity and liberty… He expressly forbade them from touching the fruit of the tree of knowledge. He wished, therefore, that man, destitute of all understanding of himself, should remain an eternal beast, ever on all-fours before the eternal God, his creator and his master. But here steps in Satan, the eternal rebel, the first freethinker and the emancipator of worlds. He makes man ashamed of his bestial ignorance and obedience; he emancipates him, stamps upon his brow the seal of liberty and humanity, in urging him to disobey and eat of the fruit of knowledge.

In his capacity as the liberator of mankind, Lucifer is in direct confrontation with the Christian god and Christ. Bilé writes that, for Nietzsche, Christianity is the rejection of everything that was great in the Greco-Roman world. The Pagan world, which Christ came to subvert, was life-affirming, “an expression of the will to power—the will to life.” Quoting Nietzsche, what replaced this world was a slave world, “emptier, paler, and more diluted.” According to Bilé, what replaced the will to life was a will to death—“antinatural, antiactual, and illogical.”

The other half of the polar equation that is the Devil is the God of Wine, of surrender, imagination, ecstasy, who is emblematic of nature itself. Bilé evokes the images of the horned gods of paganism, Pan and Cernunnos. In a passage that is far too beautiful not to quote at length, he writes:

The Devil’s forked path begins at the shores of an impossible twilight, the death-speckled blanket above that swallows the starlit gaze of the devotional. His face is terrible nature in toto; his eyes are setting suns, beaming beautiful and black as the ocean. Satan swallows the faithful; their cries of joy are rain descending upon an enshadowed mountaintop—the Crown of Heaven, and the Crowned King of damnation and death, beauty and truth, oakwood and the ashes of the desert bush…Ancient and eternal, undeniable and death-like, metaphysic and material, what Satan’s face reflects is Nature itself.

What was most valuable in ancient Paganism, for Nietzsche, was that it embraced the natural world for what it was, rather than rejecting it for an imagined world that conformed more to what we wish the world would be. This rejection doesn’t just take place in Christianity, but in many world religions, Buddhism being the most obvious. Indo-European paganism, on the other hand, venerated what was natural, strong, exuberant, and proud. Rather than hide from the bestial side of our nature, Paganism embraced it with a whole heart. For Bilé, it is the satyr-like Pan who embodies the true image of humankind, personifying “an unadorned expression of truth that exists beneath the synthetic cultural trappings” of humanity.

This Horned God, this Dionysus, this Satan, in his earthly aspect, “stands in opposition to the ‘Crucified,’ his antithesis. Life itself, with all its joys and annihilations, torment and suffering, destruction and vibrancy of life—the ‘innocent one’ represents a denial and objection to this world as-it-is, its condemnation. The Dionysian man affirms the innate viciousness of life—its tragedy; for this, he is strong, resilient, and rich in spirit.”

How to live just such a life of strength, self-actualization, and courage is precisely what Lavey set out to answer in his creation of the Church of Satan and The Satanic Bible. The above two Dionysian poles of fire and wine are very much present in Lavey’s spirituality. Through a satanic “re-reading and revaluation of Christian tradition, Satan’s negative associations transfigure into positive attribution, and he comes to embody sex, pride, rebellion, opposition, individualism, and rational self-interest.” Bilé further notes that, for Lavey, Lucifer is a bearer of knowledge—a god of invention and reason. This is the fire side.

On the wine side, Lavey’s Satan also represents the animal urges that are just as much a part of our humanity as the intellectual side. It is through this bestial side that Lavey draws a need for a “naturalistic morality.” Such a morality would not only accept but celebrate our urges for violence, pain, and physical indulgence. Such a morality, however, flies in the face of what Christianity has taught for the past 2,000 years. Bilé writes:

Lavey concedes that Satanism is “not an easy religion to adopt in a society ruled so long by Puritan ethics” and that it does not contain any concept of “false altruism” or a mandatory “love-thy-neighbor” morality. He also admits that Satanism is a “selfish and brutal philosophy” and that life is a “Darwinian struggle for survival” where only the mighty thrive and the masterful are the ones that inherit the earth…”

For Lavey, humans are predatory and hierarchical. To deny this or worse, attempt to smother it entirely, is to deny our very existence as a species. Rather than looking to an external redeemer to save us, or fool ourselves into thinking the world is anything other than what it is, Lavey challenges his followers to, “Say unto thine own heart, ‘I am my own redeemer.’” That is, to descend into reality and, through a Nietzschean transvaluation of values, affirm life in all its glory and horror.

What say you? That life is suffering and sorrow? That all the world is misery and decay? Yes, but there is leaping and dancing and laughter of the most brazen sort.

Wander! And trample the wretched who would enslave you.

Wander! And discover yourself in the flux of the world.

Wander! And let your heart sing a song of love.

Wander! And make of your death a crown. “Joy”

Leave a Reply